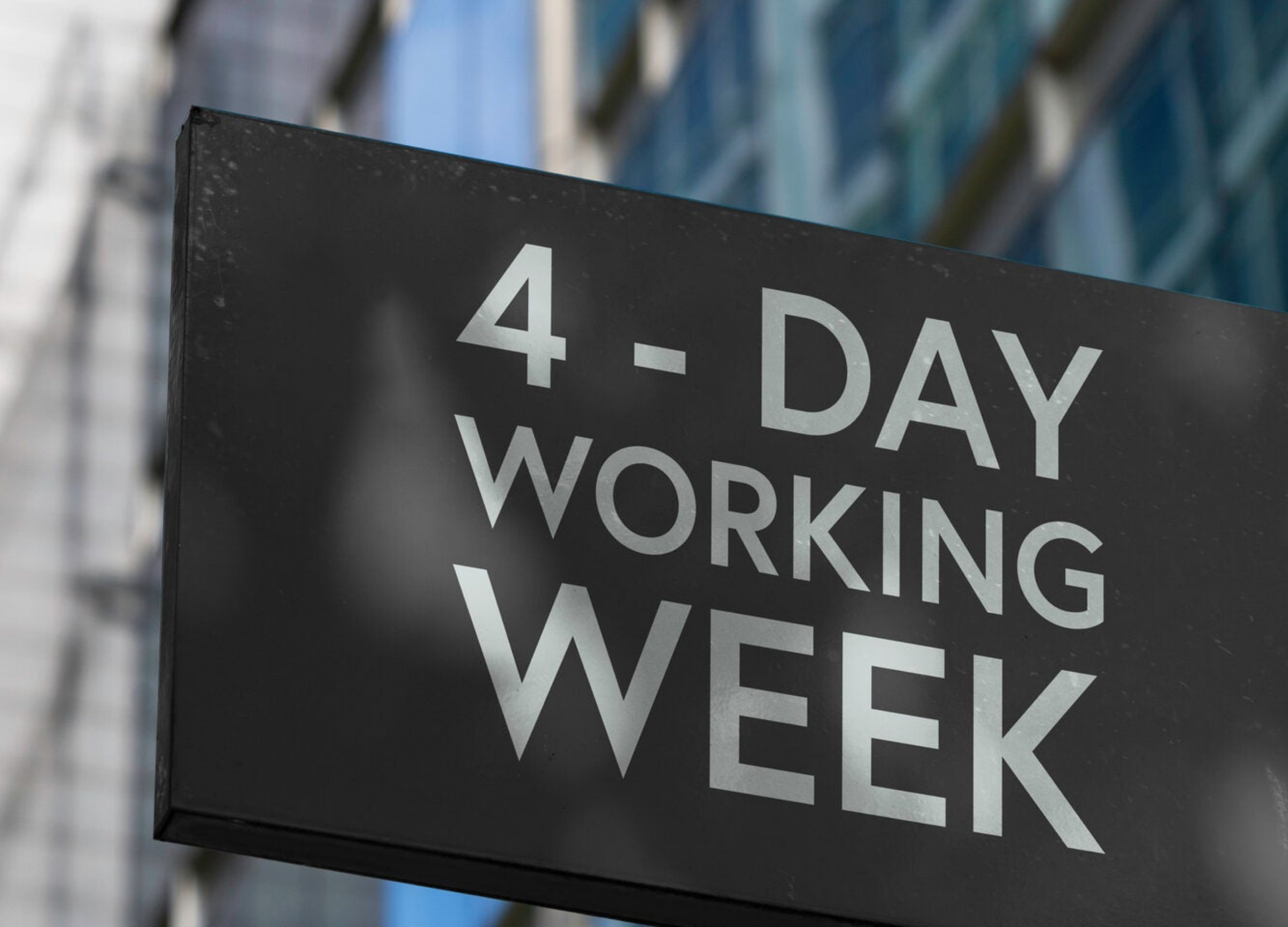

Now Reading: The Four-Day Work Week: Experiment or Future Standard?

-

01

The Four-Day Work Week: Experiment or Future Standard?

The Four-Day Work Week: Experiment or Future Standard?

What was at one time perceived as radical and thus very rarely mentioned, the idea of a four-day work week is now very often becoming part of the main discussions about the future of work. Shorter workweeks have been tested in various countries and companies around the world to see if cutting the working hours can result in the same or even a higher output with the employees’ wellbeing being improved at the same time. A four-day week is a big deal for HR leaders as they are busy deciding whether this is only a workplace experiment or it’s headed to the new global standard. Besides, how realistic, such a system would be in South Asia, including Sri Lanka, is also a big question to be answered.

Global Experiments with the Four-Day Week

Several countries have already tested shorter workweeks, and the outcomes have been quite obvious.

In a way, Iceland can be taken as an example among the biggest experiments between 2015 and 2019, where more than 2500 workers from various industries were moved. The results were very positive all over: in most of the workplaces, productivity levels were at least the same as before, while employee welfare was doubled. The staff reported that their stress levels had dropped, they were able to juggle their work and personal lives better, and their work was rewarding.

Moreover, in Japan (a country where working long hours has been the tradition), some companies have developed a four-day work week as a means of decreasing employee burnout. In 2019 Microsoft Japan accomplished a test that led to a remarkable 40% increase in productivity, and also giving the staff a feeling of motivation and satisfaction.

The same results have been found from the different trials in the U.K. which have each lasted more than six months and in 2022 when more than 70 companies signed up. These results include the control of stress and burnout among the workers at low levels from the company’s point of view while the output of work is maintained at good levels or improved as a result of the companies. A large number of organizations who decided to extend the short week or even make it their permanent schedule were those who took part in the pilot program and after it ended, they made their decision.

Those tests are indicating that a four-day working week isn’t just a whim that only the human resources department would be able to combine it with some intelligent personnel policies but that it is evolving independently.

Productivity and Employee Wellbeing

Employers’ primary concern is that reduced working hours will lead to less work. However, experiments across the globe have been a testimony to the fact that the reduction of the workday in most cases results in increased productivity. The staff is more likely to concentrate on the essential tasks, use the time wisely, and rime up their work with they colleagues. The implementation of short weeks also results in the reduction of absenteeism and presenteeism in which an employee who works after he or she is fully recharged and motivated is a cause.

Indeed, the advantages from a health perspective are quite visible. Leisure time is a great way to meet the needs for family interaction, nursing personal interests, taking care of the community, and rest. This is consistent with the Job Demands Resources (JD-R) model which highlights the need for recovery time to be able to maintain performance. The positive aspects of mental health become stronger, burnout gets less and employees become more loyal to those organizations which are considerate of their lives outside work. For HR leaders, this is transformed into higher engagement levels, lower turnover rate, and a stronger employer brand.

HR’s Adaptability to Shorter Work Weeks

Four days working with a change in the week needs a lot of HR flexibility. Processes must be redesigned so they produce the same productivity. Performance assessment should be based on the outcome of the work rather than on the number of hours spent at the desk. These areas that are necessary to be covered at all times can be a flexible schedule like a staggered four-day shift, for example.

Training managers in dealing with shorter hours, defining communication standards, and ensuring that all departments are treated equally are some of the things that need to be done. The HR team must also be ready for scenarios of a heavy workload in the four days and employees not really getting the intended benefits of the four-day work week if they are not adequately managed.

The South Asian and Sri Lankan Context

A large-scale global experiment was conducted, and the results turned out to be quite good. However, the introduction of the four-day work week in South Asia should only take place after it has been ensured that the local conditions have been properly understood.

Sri Lanka is still dominated by sectors where most of the employees measure success by the time spent in the office. For these workers, going to the office has become the main criterion of productivity rather than the work results. A reduction of the working hours without reorganization may cause these companies to stop their activities in such industries as manufacturing, retail, and public service. Besides, in the middle of economic problems that may result in a crisis, some entrepreneurs might consider that the way to survive is to put the business hours up instead of finding other solutions.

While this is going on, the IT, finance, and knowledge services sectors could be the only ones that welcome firmly such an experiment with a positive attitude. They are already very digitalized when it comes to the workflow, they are project-based, and are unreservedly connected to the rest of the world. Especially for young professionals, it cannot be more true that the four-day week could be one of the strongest factors in the decision to come and remain in that company.

It is quite expected that if the information about shorter working weeks would be properly communicated in South Asia, employees would embrace such a change with open arms as they are people who still adhere to the principle of collectivism and for whom the notion of family and community is very dear to their hearts. Nevertheless, the issue remains as to whether the managers will be willing to move from the conventional ‘management by fear’ method to a functional management system.

Experiment or Emerging Standard?

The four-day work week is still an experiment in much of the world, but the results so far are promising. Evidence suggests that organizations can maintain productivity while significantly improving employee wellbeing, provided the model is implemented thoughtfully.

News about shorter working weeks in South Asia where people are the ones still living by the principle of collectivism and for whom the idea of family and community is very close to their hearts is highly likely to result in employees being more than happy to accept such a change. However, the problem is whether employers are ready to give up the traditional ‘taking care of the presentiment way’ and go for a performance-based model.

This adaptation will not be uniform across sectors, but knowledge-driven industries could be the leaders in this transformation, as said by Sri Lanka and other South Asian economies. The secret to the success of HR is their ability and willingness to rethink workflows, measure outcomes instead of hours and build cultures that value recovery as much as the effort put in.

The four-day week is more than just a change in scheduling; it signifies a fundamental shift in our perception of work and success. The future of the standard it might become will largely depend on how ready organizations will be to challenge tradition and accept innovation. In Sri Lanka, the talk is at the very beginning stage, but it could be a very effective way of getting to healthier and more resilient workplaces.